And now we reach what is, beyond the slimmest shadow of a doubt, the coolest shit I have seen on this entire roadtrip.

(Also Happy Belated Birthday to my best friend in the whole wide world, Andrew Glenn 💙; I know you’ve been reading up on Native American history recently so I hope you like this post)

When I left the Grand Canyon, I moved on to the Four Corners Region (that part of the Colorado Plateau where Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah all meet) in order to see Mesa Verde National Park, Canyons of the Ancients National Monument, and Chaco Canyon National Historical Monument. This isn’t an area of the country I have thought about much (it’s a long ways from any interstates and big cities) but in general the area is pleasant, pretty, and verdant, especially in spring:

Sleeping Ute Mountain: the Ute Tribe, who have a reservation in this area, believe that this mountain is the final resting place of the warrior diety of the same name.

However, the main reason this area is special is the large number of Native American archaeological sites found in the aforementioned national parks and monuments. I was extremely amazed by these sites, and I will reflect that in how I write this blog post, but I want everyone to understand that this is coming from a place of “I can’t believe we never learned about this in school!” and not “I can’t believe the ancient native Americans figured out how to do this!” This is an important distinction. Too often, and for reasons that range from lack of education to outright racism, modern observers don’t give Native Americans the assumptions of competence and understandings of science and engineering that most other pre-modern societies get. But engineering, and architecture, and construction are all the daughters of physics, and physics works the exact same way all over the world; therefore, we should expect nothing less than that the Native Americans would build great and impressive buildings, just like the Egyptians, and the Chinese, and the Zimbabweans. It’s just what people do and we can all figure out how to do it.

No, my amazement comes from the fact that so much incredible pre-columbian native history was completely ignored in all my education growing up. In Michigan, when you learn about the Indians in Michigan in about fourth grade, all you learn is “The Chippewa, the Ottawa, and the Potawamani [digression: these are not what these people call themselves] lived here once! But everything they built was made of sticks and buckskins, so nothing survives and we know nothing about them.” This is bullshit – the Midwest is littered with permanent earthworks like Cahokia and Snake Mounds, and even Michigan is home to the Sanilac Petroglyphs and other impressive native archaeological sites. And if you take AP US in high school? If you’re lucky, you’ll get a passing mention of “the mound builders”, but that’s it.

So that real history of Native America, that doubtless proof that Native America predates and preempts the USA, finally seeing the evidence for that in person is why I was so awestruck when I saw stuff like this:

This is Escalate Pueblo in Canyons of the Ancients National Monument near Cortez, CO; it was inhabited by 50 to 70 ancestral puebloans in the mid 1200s. Just look at this! Real stone construction, including large public spaces and interconnected private dwellings!

This is absolutely incredible, and it’s, just like, in the equivalent of a county park! There aren’t any teams of archeologists painstakingly dissecting these ruins, there aren’t “KEEP OUT” signs or fences up for observers, this is just around! Like it was an old and weathered homestead! And it was the most intricate and impressive ancient native site I had ever seen!

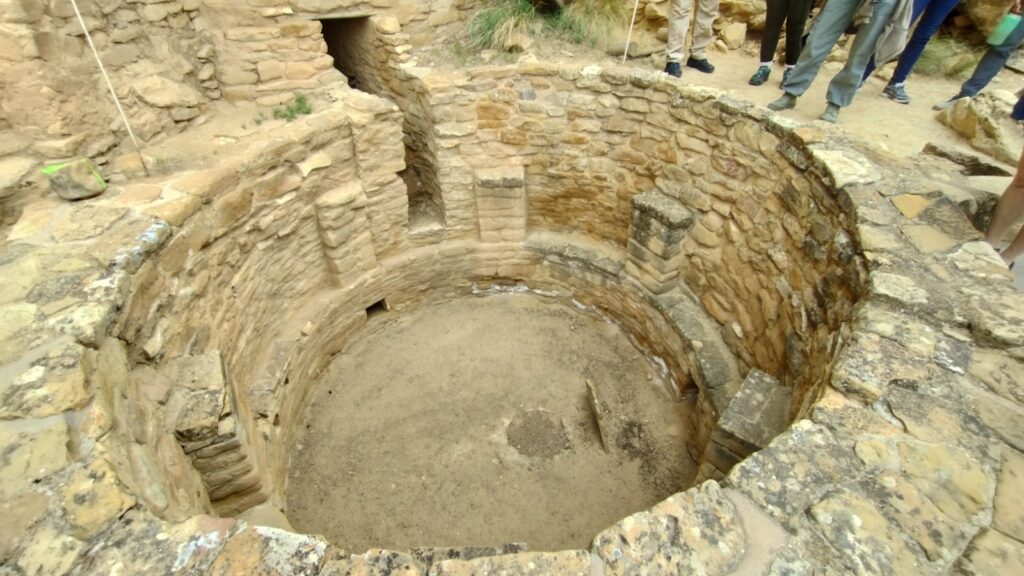

Here is Escalate Pueblo’s Kiva, a commonality among ancestral puebloan sites. Depending on when they were built and who was building them, Kivas were used for both practical purposes (common areas, a cool retreat in the summer, also as a cook shack, etc.) and religious purposes (discussed latter). Kivas are dug 6-8 feet into the ground and typically had a timber structure that supported a flat, dirt roof, creating a plaza space on top; access was via a ladder through a hole in the ceiling, which also served as a smoke hole for the hearth within the Kiva. By being buried underground and having an earthen ceiling, Kivas had enormous thermal mass that kept them cool in the summer and warm in the winter.

I thought this was the coolest archeological stuff I had ever seen. But boy were my standards about to be blown to smithereens:

Because here is Lowry Pueblo, and you can actually go inside this one!

Look at how amazing this stonework is! 800 years later and the walls have barely settled or sagged, they’re all still fit perfectly into place and mortared together!

Here is Lowry’s central Kiva, and look! It still has original timbers in there! “Sticks and buckskins” this is not!

Lowry Pueblo also has a Great Kiva some distance away from the main settlement. The huge stone effigies in the floor of the great kiva probably indicate that this was used for ceremonial purposes in addition to pragmatic ones. Also, this thing is huge, it’s easily 50 feet in diameter. And to imagine that there was a roof on this at one point!

But my expectations just kept getting blown apart! The next day I went to Chaco Canyon National Monument and I was utterly awestruck by that I saw there:

This is Pueblo Bonito, the largest ancestral puebloan site discovered. It covers 3 freaking acres and contains over 600 rooms. And you can walk through many of them! Just look at how incredible this architecture is!

Many of these rooms have the ends of their original ceiling beams still in place in the walls! Just look, they use installed large logs as stringers over the width of the rooms, then ran smaller logs as stiffeners over the length of the room! This is exactly how I design the structures of longitudinally framed ships today!!! It’s also brilliant to put the larger logs over the width of the room, since it shortens their length and reduced the total length of heavy lumber needed, an important factor given that these logs were being hand-dragged from forests over 100 miles away (according to the museum placards).

Some of sections of Pueblo Bonito are 3 stories high! Actually, most of the rooms I took these pictures in were originally 5 whole stories high! With two stories being built underground:

Above is an example of having two additional stories constructed underground. Most of these lower levels are back-filled after being excavated to maintain the stability of the supporting walls.

Some of the rooms are so well-preseved that we can actually see the adobe flooring that was installed, in order to create a flat floor and add thermal mass:

You can even see in the area above that internal walls were frequently plastered! And while it does not survive as often, other archaeological evidence says that these walls were often painted, sometimes 40 layers deep over the centuries. Pardon my French, but this shit is insane!!!

The entire shape of Pueblo Bonito is of a huge semicircle with a main central plaza and individual rooms encircling. The complex is believed to have been built in bits and pieces over hundreds of years (from the mid 800s to the mid 1100s), but it shows consistent elements of a central design plan; for example, the front face of the Pueblo is aligned exactly east to west, and petroglyphs on the canyon walls beyond mark the positions of sunsets and sunrises on the solstices. Even the hemispherical shape is maintained in the outer rooms, as seem below:

These doorways between private residences follow the overall arc of the hemisphere seen from the air.

“T-Shaped” doorways are built at the thresholds between public and private spaces, whereas doorways from one private space to another are usually just rectangular.

Doorways usually had timber framing over the top for support. Dad, notice the corks? Where scientists drilled into the timbers to take samples and analyze their age, they stuck corks back into the logs to protect them from bugs and rot; just like we did with the maple trees we tapped for sap back in the day!

Pueblo Bonito also has dozens of Kivas. Many of the smaller kivas are suspected to be used for practical purposes and constructed and maintained by family units or clans:

You can see other, adjoining kivas in the background. Even the smaller kivas are deep enough to suggest that they may have had multiple levels or a kind of sub-flooring just above the Earth.

But it also features two huge, parallel, great kivas in the main plaza:

Just look at how insanely intricate these are! And they’re over 75 feet across! And remember, these kivas were flat-roofed and used as a public terrace! Here is a model of a nearby great house up the canyon that shows what the roofed Kiva looked like back in the day:

The meaning of the effigies in the floor, along with the hearths, fonts, and intricately places stones in the great kivas, is largely unknown. One native visitor from Taos Pueblo to Lowry Pueblo remarked that the effigies might represent summer and winter peoples, and it’s believed that the ceromial/religious purposes they might have had are similar to those of modern Puebloans, as well as the Zuni and the Hopi tribes.

That’s another fascinating aspect of Pueblo Bonito; we don’t know who exactly inhabited it or what their usage patterns of the site was. While there are over 600 rooms in Pueblo Bonito, at first suggesting habitation by hundreds of families and thousands of individuals, less than 100 hearths have been uncovered. Trash heaps outside the village are also not nearly as large as a population of several thousand people would be expected to produced, and historians now estimate that less than 800 people lived in the Pueblo year-round. More likely, Pueblo Bonito was a gathering space where communties from around the Colorado plateau would come for ceremonies and festivals. This is also supported by LIDAR findings of roads that extend radially outward from Pueblo Bonito to communities over 150 miles away.

And this blew my freaking mind: Macaws??? Traded as pets??? All the way from Central America??? Pueblo Bonito appears to have been an enormously important trading hub, hundreds of years older than the Aztecs and spanning the freaking continent, and yet we learn nothing about this in school!

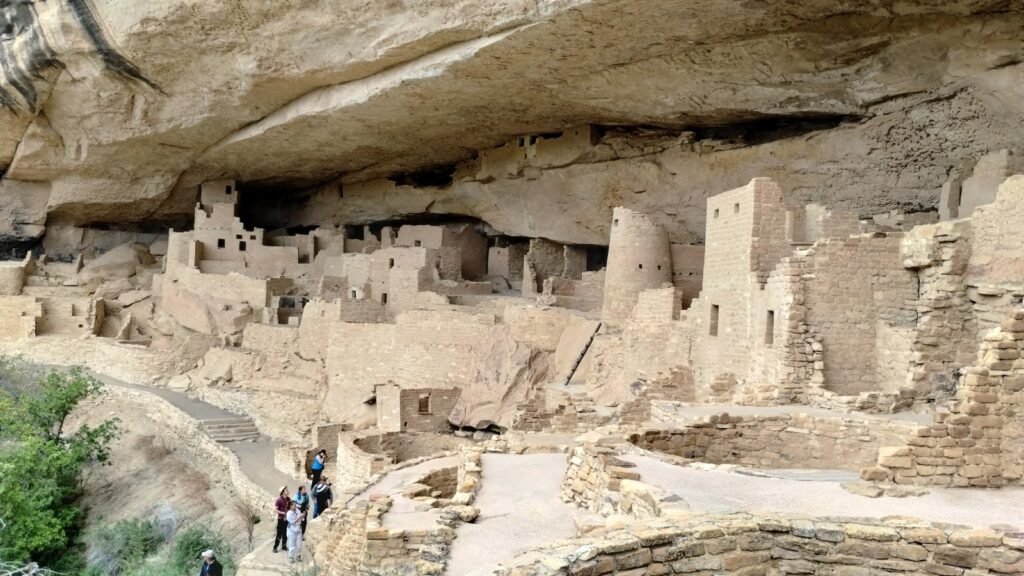

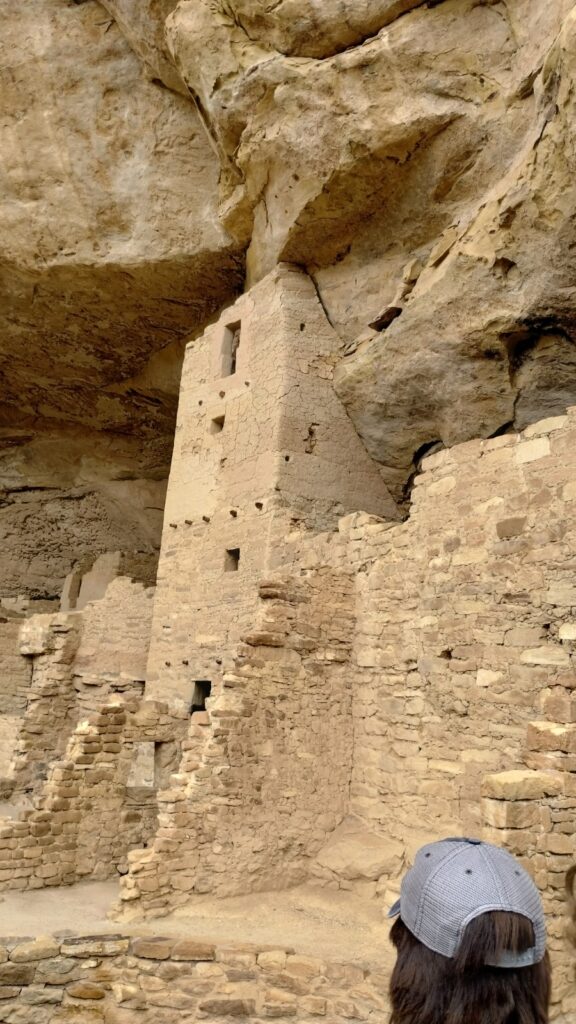

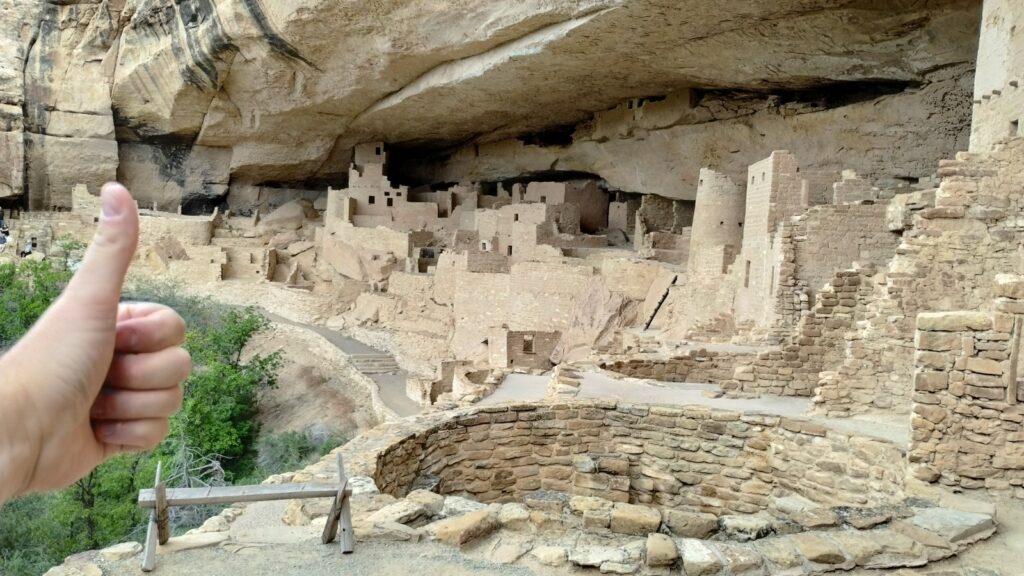

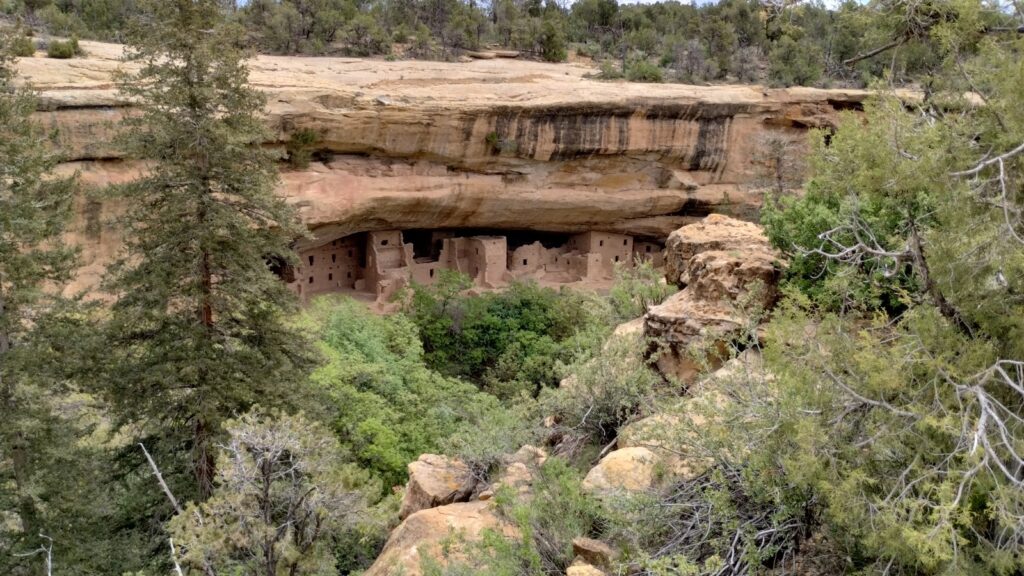

But friends, it just keeps getting more impressive. The next day I finally got into a tour of the Cliff Palace at Mesa Verde National Park, the final Ancestral Puebloan site on my list of things to see. I think you guys understand my level of amazement at all these sites, so I will just let the photos do the talking. It’s more fitting that way, especially considering I was speechless (which is very rare!) when I saw this in person:

GUY! IT’S AN ENTIRE SETTLEMENT FOR 600+ PEOPLE BUILT UNDERNEATH THE SIDE OF A CLIFF! HOW CAN IT POSSIBLY GET COOLER THAN THAT?!

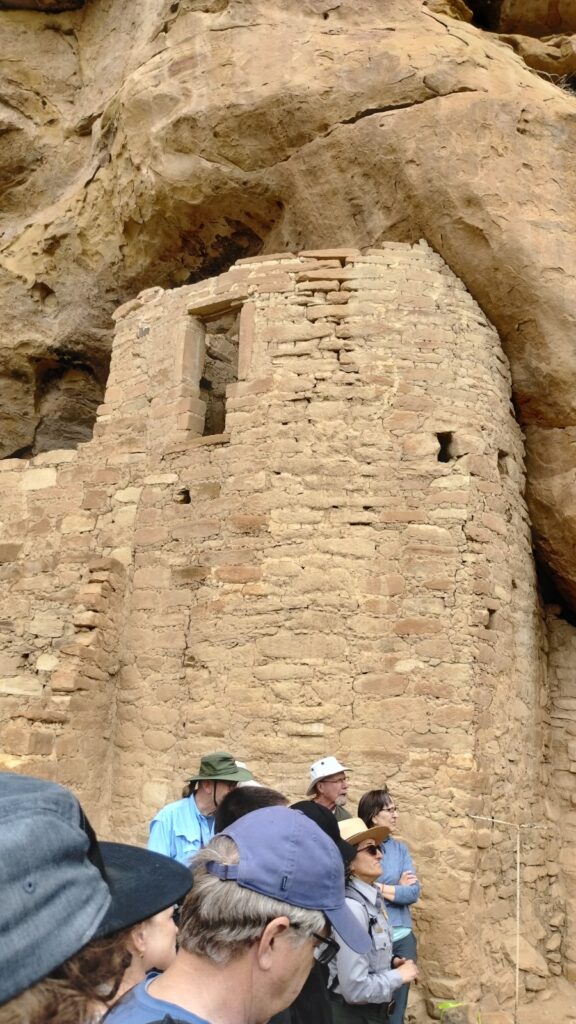

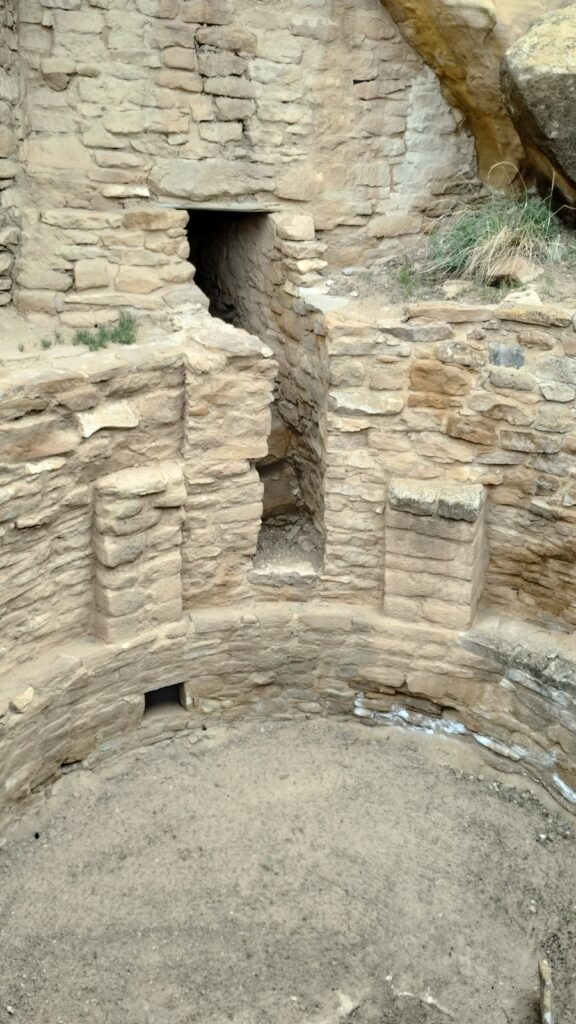

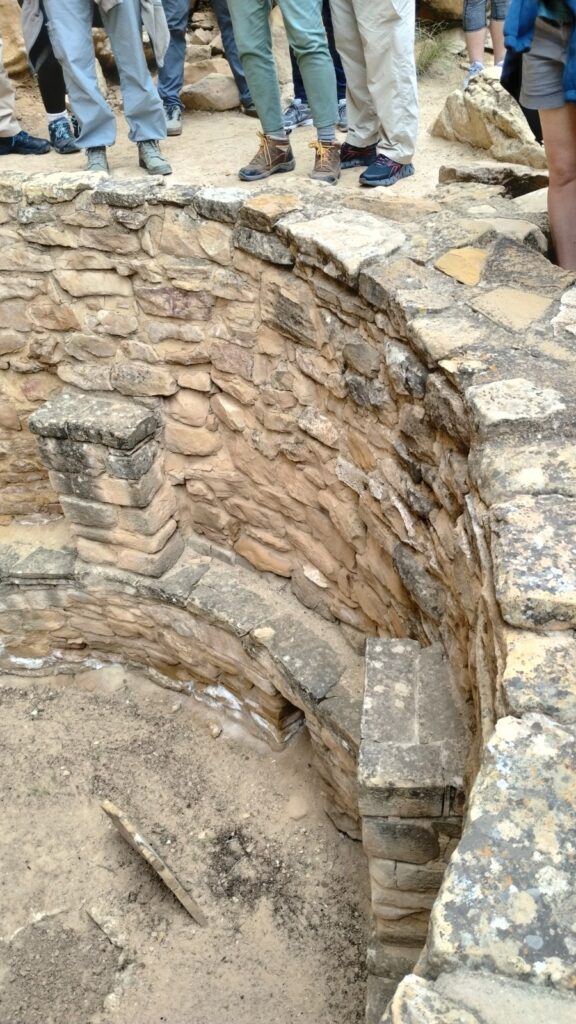

Cliff Palace was inhabited from the mid-900s to the mid-1200s, and bears some similarities and some differences to Pueblo Bonito, 85 miles away as the crow flies. One of the key differences is that Kivas at Cliff Palace are all built from the ground up, since it was more difficult to excavate the sandstone of the cliff:

Incredibly, these Kivas have connecting paths and chambers that draw air warmed by the hearth into the rooms near the Kiva, creating a system of central heating:

Even more impressively, the Kivas had a separate ventilation shaft for fresh air to enter the Kiva behind the hearth:

The hole at ground level in the middle of the photo is the entrance of the ventilation shaft, while the flat stone sticking up out of the ground in front of it is a deflector, which ensures that the draft of air doesn’t extinguish the fire in the hearth or smoke out the Kiva. This is essentially the same principle of circulation used in the Franklin Stove, which wasn’t invented until 1742! This was more modern HVAC than anything the colonists devised for hundreds of years.

Lastly, while there aren’t many excavated examples of this, most kivas at Cliff Palace had a clay-lined divot in the floor of the kiva, or sometimes an entire pot buried in the ground with just the neck exposed and flush with the floor. This represented a religious, and frankly very literal, connection to mother Earth, interpreted as a navel from which the ancestral puebloans had sprung, and into which religious offerings were often placed. I don’t know why, but I found this symbolism deeply compelling.

While not open at this time, Mesa Verde also has Spruce House, which even has kivas with fully reconstructed roofs:

You can’t get very close to it because it’s closed to the public, and the zoom on my camera is pretty poor, but I did manage to get some cool close-up photos through the lens of my binoculars:

You can see the Kiva’s flat roof and the entryway with ladder installed.

Amazing petroglyphs are nearby too.

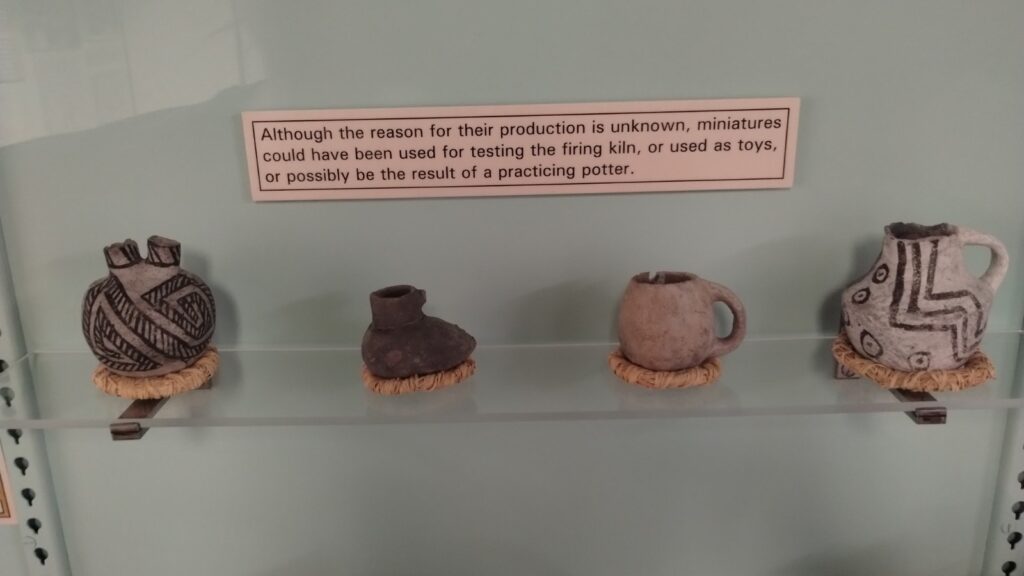

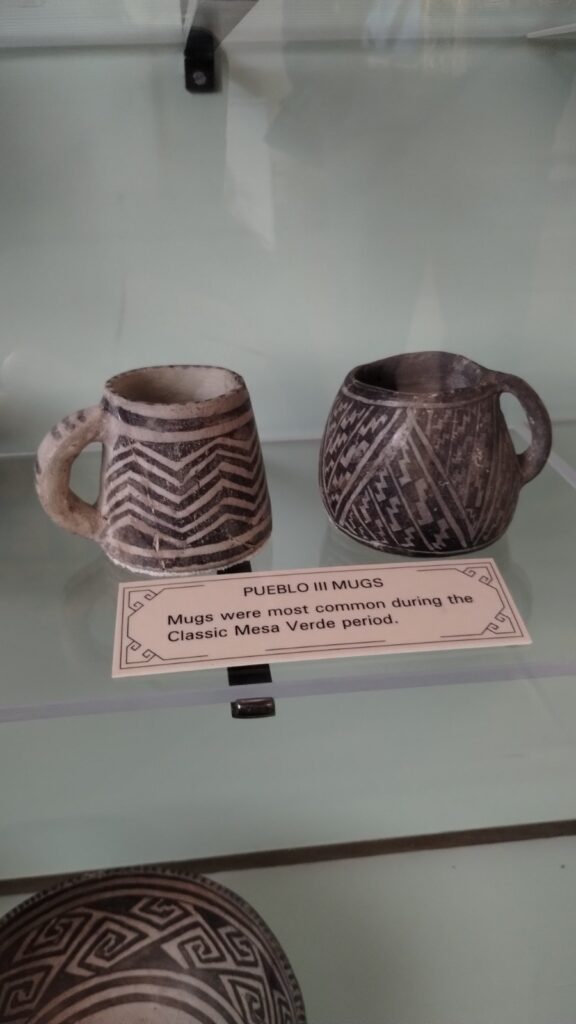

The last thing I will say about Mesa Verde National Park is that it also had an amazing collection of artifacts from Cliff Palace and the other sites in the area (yeah, there have been over 500 archaeological sites discovered in the park, which is insane). Albeit the full collection is actually smaller than you would expect, apparently because the site was pillaged by a bunch of scurrilous Norwegians before the area was made into a national park:

Dan: the instrument seen above is, in fact, used for grinding corn, and not as a chair.

And here is the corn that was ground in it. Not figuratively; this corn is over 700 years old and was literally pulled from a jar buried into the ground. Isn’t it amazing that this survives?

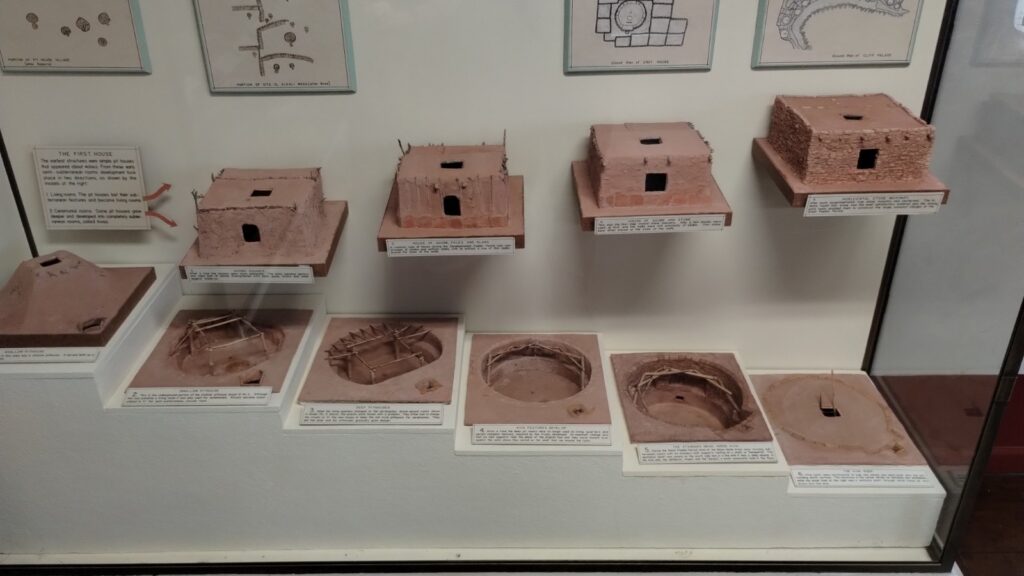

Apparently both underground kivas and above-ground adobe homes evolved from a single, original dwelling: the semi-subterranean pit house (at left).

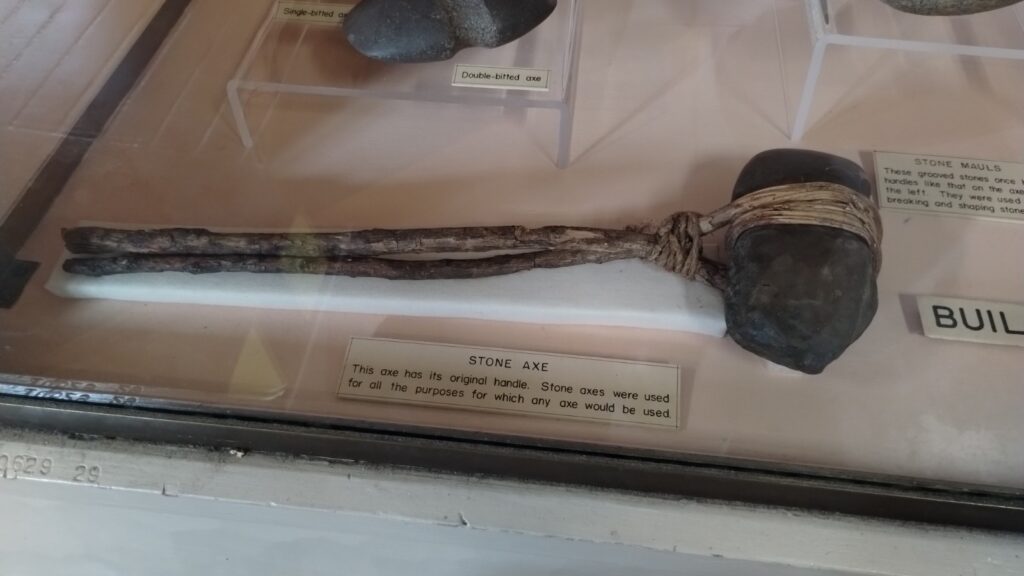

I thought this was an extremely clever way to haft an axe head to its handle using one continuous branch for the handle, and pounded flat where it needs to loop around the head.

Guys, if you decided to see just one group of things that I talk about in this entire road trip, let it be the four corners region and the Puebloans sites there. This is the coolest historical stuff I have ever seen in the United States, and I live next to DC, this is a fierce competition for a history nerd like me.

Pueblo Lowry, Cliff Palace, Pueblo Bonito: see them before you die.

But eventually I read just about every placard, and asked every question of the rangers, and basked in awe of every site I could access in this corner of the USA: only then was it time to move on from all this amazing history we never learned in school.

I would be remiss if I wrote an entire post about Native American history without taking some of that history to the present day. In traveling from the Grand Canyon up to Cortez, then down to Pueblo Bonito, and then west again towards Zion, I crossed both the length, width, and diagonal of the Navajo reservation. Note that the Navajo are not descended from the Ancestral Puebloans, and appear to have moved into the area several after the departure of the Ancestral Puebloans. This have have been a violent exchange, as the Navajo word Anasazi for the modern Puebloan peoples means “Ancient Enemy” (the modern Puebloans themselves are not a unified tribe, by the way. As explained to me by a guide who grew up in Taos Pueblo, Puebloans peoples share similarities in culture, religious beliefs, and architecture, but speak several different languages and do not represent a unified ethnic group). While traveling on US-160 west of the town of Tsegi, I saw some incredible artwork on some abandoned buildings surrounding an equally abandoned gas station:

An older Navajo man named Stanley had also stopped at the gas station for a break from the road. He saw me taking pictures and struck up a conversation, and told me about the history of the area. The Navajo reservation has several coal mines, and there was a coal elevator and a railhead nearby to support one of these local mines. Well, despite his promises about putting coal miners back to work and making America energy independent again, when this Navajo coal mine fell on hard times in 2018, Trump did nothing to help keep the mine afloat. The mine shuttered in 2019, and when the elevator and railhead went with it, the very town Stanley and I were standing in the middle of was completely abandoned. The empty buildings were painted by a local artist a short while after that. “I stop here sometimes and think about when this place was so busy. I’m watching my grandkids today, so I stopped so I could show them that history too. I’ve still got a lot of family in the area; my grand-nephew’s graduation was up the road just yesterday.”

I thanked Stanley for the history lesson and waved him and his grandkids goodbye. I thought a lot about what he said. It reminded me that native history isn’t ancient history; it continues, and will always continue, here and elsewhere, every day.

Stay well everyone,

Evan 💙

P.S. Alright I don’t want to end on a totally pointed note so here is something funny I saw at a gas station in Page, Arizona:

Cherry Hot Koolaid Pickle?? Eugh! How gross does that sound, right?? 😂

P.P.S. Sorry for how long it took for this post to come out, it took me a while to get all the photos uploaded, and I haven’t had great internet access for the last week or so. Next update will be about some places and people that are very special to me (yup, that’s you, Marieka and Sam and Poppy 💙 Thank you so much for letting me crash at your place!)

P.P.P.S. Join my postcard club! See my “one month on the road” post for details!